Gold jewellery has been found to be a favoured mechanism for money and gold laundering, particularly in Latin America. For example, in 2019 the Colombian Attorney General’s Office uncovered a gold trafficking operation that moved more than 19 billion pesos worth of pure Colombian gold bars to Panama in return for Italian gold jewellery. This jewellery was then smuggled back into Colombia, where the leaders of the criminal operation distributed and sold the jewellery, effectively laundering large sums of narcotics proceeds. The operation was carried out by human couriers with assistance from immigration officials.

Launched in January 2016, Operation Diez Condores was a joint investigation by the FBI and Chile’s Investigations Police that dismantled a Chilean transnational criminal organisation (TCO) smuggling illicit gold. The TCO sourced gold from illegal operations, created fraudulent origin documents, and hand-carried the gold to the US, where it was sold to NTR Metals Miami, a refinery that wired payments back to Chile. The scheme moved US$80 million through shell companies before Chilean authorities arrested the TCO members in August 2016. Evidence revealed that NTR executives knowingly facilitated transactions involving illicit gold tied to Organised Crime across Latin America. The case expanded to include US and Peruvian investigations, culminating in the 2017 convictions of three NTR executives, seven total subjects, and over US$40 million in restitution. Widely recognised for exposing how TCOs use illicit gold to launder profits, it is one of the largest Money Laundering cases ever prosecuted in the Southern District of Florida.

The Pascua-Lama mining project, straddling the Chile-Argentina border in the Huasco Valley of the Andes, demonstrates the severe environmental and social conflicts that can arise from large-scale mining operations in ecologically sensitive areas. After more than two decades of legal challenges and public protests, Chile's First Environmental Court ordered the definitive closure of Canadian mining company Barrick's Chilean operations in September 2020, imposing a US$9.7 million fine for 33 violations including contaminating the vital Estrecho River without notifying local communities and inadequately evaluating impacts on Andean glaciers. The mine posed particular environmental risks due to its proximity to three glaciers and two rivers in the UNESCO San Guillermo Biosphere Reserve, with evidence showing that exploratory drilling had already disrupted groundwater filtration processes, allowing contaminated water to enter nearby rivers that are crucial water sources for Indigenous Diaguita communities and other local farmers in the arid Atacama Desert region. Despite this unprecedented legal victory for environmental defenders and Indigenous groups who had organised transnational resistance since the project's inception in 1994, Barrick continues to conduct investigatory drilling in the surrounding area.

Chile has emerged as a strategic exit point for illegal gold smuggling from South America to Dubai, exemplifying how criminal networks exploit regulatory gaps across continents to profit from illicit mining. In 2021, law enforcement operations uncovered a sophisticated "Gold Cartel" comprised of the Farías, Herrera, and González clans who smuggled over 500kg of gold to Dubai, resulting in the seizure of multiple properties, vehicles, and currency worth over US$500 million. The case of Harold Elías Vilches Pizarro particularly illustrates the scale and profitability of these operations – at just 20 years old, he established an extensive trafficking network that moved approximately 1,800kg of gold worth US$80 million, primarily to Dubai, using falsified documents to conceal the illegal origins of the minerals sourced from Peru and Bolivia. Chile's response has been inconsistent: while authorities have implemented blanket regulations since 2016 requiring detailed reporting from precious metal importers, the lenient sentences for convicted traffickers – such as Vilches Pizarro receiving only five years of house arrest with supervised freedoms despite orchestrating an US$80 million operation – raise questions about the deterrent effect of current enforcement mechanisms on illegal mining and mineral trafficking through the region.

In 2023, Chile's environmental regulator, the Superintendency of the Environment, filed four charges against Anglo American’s Los Bronces copper mine for noncompliance with environmental permits, potentially resulting in fines of approximately 17 billion pesos (US$17.17 million). The most serious charge stems from the company's decade-long failure to implement a definitive solution for acid drainage issues at the Esteriles Donoso tailings deposit, constituting a "repetition of acts previously sanctioned" dating back to 2014. Additional "serious" violations include failing to design a mitigation system for acid waters collected downstream of the Esteriles deposit and not taking adequate measures to control seepage in the Las Tortolas tailings dam, while a "minor" charge was filed for incomplete reporting of water and tailings data. This case highlights the persistent environmental challenges facing copper mining operations, particularly regarding the management of toxic mine waste and water contamination, as well as regulatory efforts to enforce compliance through escalating sanctions – an especially significant development considering Los Bronces' strategic importance to Anglo American, which has been targeted for acquisition by mining giant BHP.

According to a report by INTERPOL, Organised Crime groups exploit African airlines and airports with low screening facilities to smuggle illicit goods. Thanks to weak control and probable corruption, criminals can move large amounts of gold via commercial flights. In August 2019, for example, 60kg of gold hidden in parcels containing passengers’ blankets were seized and a transnational criminal network was dismantled. In another case, a Chadian trader tried to export 20.1kg of gold from Cameroon in a false bottomed suitcase and was arrested in Douala. These groups also use private planes to smuggle large quantities of gold, as these planes are not always physically checked by customs. In 2021, open sources reported that Cameroon’s authorities arrested two Canadians and a Cameroonian national who were about to smuggle 250kg of gold to the United Arab Emirates using a private jet.

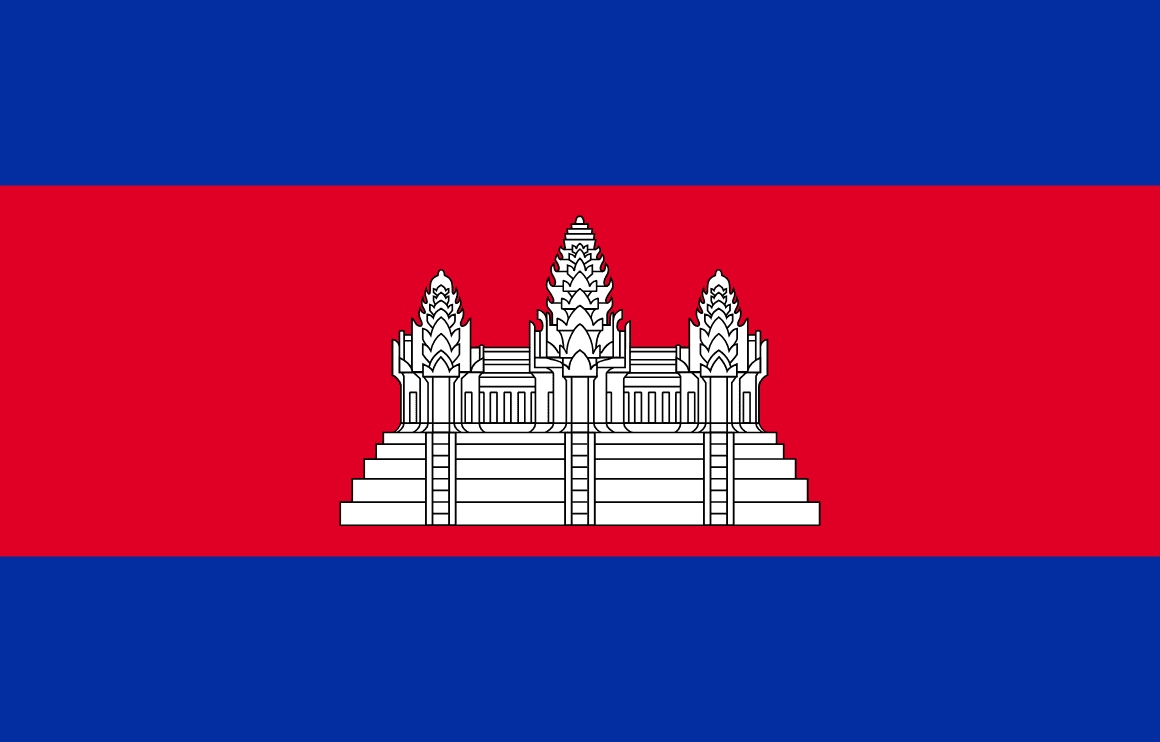

In 2023, an Australian mining company, Oz Minerals, which was being investigated by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) over alleged foreign bribery, agreed to confiscation orders to the value of at least AUD$9.3 million. Oz Minerals Ltd self-reported to the AFP that employees of Oxiana (Cambodia) Limited, a foreign subsidiary of Oxiana Limited that later became a part of the Oz Minerals group, may have bribed foreign officials to obtain gold and copper mining rights in Cambodia between November 2006 and October 2009. The company agreed to a payment of a pecuniary penalty of AUD$3.65 million and forfeiture of AUD$5.71 million received by the company pursuant to the sale agreement.

While illegal gold mining is less prevalent in Cambodia than larger-scale regulated operations, it is nonetheless often linked with environmental degradation and pollution. Furthermore, legally mined gold is often smuggled by criminals across borders for sale at a profit, particularly as gold prices in Cambodia are lower than neighbouring countries such as Vietnam. In 2024, Cambodian officials prosecuted numerous individuals for smuggling six tonnes of gold – worth around US$335 million – from Cambodia to Vietnam. The smugglers purchased gold from shops at a market in Phnom Penh, before storing it in hidden compartments under wheelbarrows that carry ice and smuggling the vehicles to an ice-making workshop in Vietnam.

Late Cheng Mining Development, a Chinese-owned company, has been operating a gold mine inside Cambodia's Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary since early 2019, well before receiving their exploratory licence in March 2020 or extraction licence in September 2022. According to local villagers and satellite imagery analysis, the company began industrial-scale operations in early 2019 by taking over what was previously a smaller artisanal mining site. The company has diverted local streams for cyanide leaching to extract gold, potentially contaminating the Porong River which flows into the Chinnit River, a tributary of the ecologically important Tonle Sap Lake. Despite operating in a protected area that houses 55 threatened wildlife species and 80% of Cambodia's endangered indigenous trees, Late Cheng has expanded from 1,900 to over 4,200 hectares in 2023 alone, with leaching ponds now spilling beyond their concession boundaries into previously untouched forest.

In March 2025, Cambodian authorities in the Ratanakiri province uncovered and shut down illegal gold mining operations in the Ta Veng District, arresting 26 Vietnamese nationals who were subsequently deported through the O'Yadav international border without facing legal prosecution. The mining operations, which took place within Virachey National Park (a protected area bordering Vietnam and Laos), involved heavy machinery including excavators that were confiscated during the raid. While provincial Mine and Energy Department director Ung Hou claimed the sites were "licensed" but not following proper procedures, other officials revealed the miners had entered Cambodia legally with passports but were working for a company that had obtained land concessions for rubber plantations before illicitly converting operations to gold mining without proper exploration permits. Environmental advocates expressed concern about the scale of these operations and the likely use of cyanide for gold extraction, which poses severe risks to waterways, biodiversity, and human health in the region. Despite laws stipulating fines of 1-10 million riel and imprisonment of 1-5 years for illegal mining in protected areas, the case was handed to immigration authorities rather than processed through the court system, highlighting enforcement inconsistencies in Cambodia's mineral resource management.

In 2023, Mongabay published an article detailing how the Late Cheng Mining Development in Cambodia demonstrates the role of political connections in enabling illegal mining within protected areas. The company’s chairman, Zhao Yingming, had been photographed alongside Prime Minister Hun Manet and the former commander of the Prime Minister's Bodyguard Unit. He was also shown to have business ties with Chun You, a deputy director-general at Cambodia's Ministry of National Defence, who chairs a neighbouring mining company – Cambodian K88 Industry – that received its license just 18 days after Late Cheng. This web of connections appears to have enabled Late Cheng to operate for roughly 18 months without a legal extraction license, bypass environmental impact assessments, and evade enforcement of Cambodia’s Protected Area Law, which prohibits activities such as water contamination and chemical waste disposal in protected zones. Villagers who have raised concerns about environmental damage and land loss report that their complaints have been ignored by authorities.

According to a report by the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, jihadist groups are reported to control gold sites in northern Burkina Faso, levying taxes and protection fees from gold miners. Taxation and protection fees are not always viewed as oppressive by the local population. Local gold miners can see these practices as democratisng access to gold mine sites previously controlled by actors with powerful political connections. Protection may even be solicited by miners, sometimes in response to crackdowns on ASGM by the state. However, the refusal to make payments can have dire consequences. In June 2021, in the deadliest attack to date in Burkina Faso, insurgents attacked the gold-mining community of Solhan, in the Sahel region, killing at least 132 civilians. It was reported that jihadists targeted the site after Koglwéogo, a local self-defence group, secured the mine site and refused to pay protection fees or any other payments to the group.

Conflict between industrial mining operations and local communities in Burkina Faso has been exacerbated by instances of artisanal and small-scale gold mining (ASGM) operations, sometimes consisting of tens of thousands of people being forced off land so that industrial mining operations can proceed. In the city of Houndé in May 2022, significant tensions between artisanal miners and industrial mines escalated to violence following government efforts to clear ASGM miners from a Houndé gold site for an industrial mining operation. ASGM miners claimed they had been working in the area first and the violent protest that ensued resulted in the deaths of two miners. Such tensions are exacerbated by the presence of terrorist groups’ involvement in gold mining: In 2018, the governor of the Est region ordered the closure of artisanal mining sites to cut off sources of funding for terrorist groups. Consequently, disgruntled miners turned toward jihadists, who reopened certain mines. Similarly, in the Soum province, in the Sahel region, communities appear to have been brought closer to jihadists following counterterrorism operations in early 2019, during which gold mining equipment and gold were seized by state security forces.

According to an investigation by AP, sex trafficking is widespread in Burkina Faso. Those with knowledge of the trafficking say most of the women come from Nigeria’s Edo state, where promises of jobs in shops or salons in Burkina Faso seem like a good way to support their families. Once in Burkina Faso, they are sent to work off debts in squalid conditions of forced prostitution at or near small-scale gold mines. One man arrested and detained by local authorities for trying to traffic three women across the Burkina Faso border into neighbouring Mali told the AP he didn’t consider it Human Trafficking because he said the women knew they’d be working as prostitutes. He told the AP that he had bought the women for US$270 each in Benin and was planning to sell them for more than twice that to a Nigerian madam in Mali. Experts and local officials say most documented Human Trafficking cases of women appear at small-scale gold mines rather than the larger industrial mines. Nonetheless, in one now-vibrant mining community, the southwestern town of Hounde, the opening of an industrial gold mine in 2017 led to a six-fold increase in brothels.

In September 2024, Brazilian police carried out a wide operation against illegal mining in the Amazon, raiding a criminal organisation that allegedly financed the production and sale of 3.1 tonnes of gold, which was then laundered with the assistance of fraudulent papers. Much of the gold was refined in Sao Jose do Rio Preto, a city in the north of Sao Paulo state that has a thriving jewellery industry and where illegal gold is often melted down into ingots with legal gold, making it harder to trace the illegal metal. A federal judge ordered the confiscation and freezing of 2.9 billion reais (US$514 million) in cash and assets, including vehicles, motorcycles, jewellery and gold nuggets. Furthermore, local police stated that as a result of the operation, four companies were suspended, six mining licenses and four gun possession permits were revoked, and four local government officials were ordered removed from office, suggesting potential Corruption & Bribery.

In 2019, Brazil’s Brumadinho dam - a tailings (mining waste) dam owned and operated by Brazilian mining giant Vale - collapsed, leading to 270 deaths and millions of tonnes of toxic waste being leaked into the surrounding area. In the aftermath of the event, Vale was ordered to pay US$7 billion to affected communities, and Brazilian prosecutors have since charged 16 people – including Vale’s former CEO – with murder and Environmental Crimes, alleging that Vale was aware that the dam was unstable yet neglected to address risks in order to avoid negative reputational impacts that could affect market value. The legal process remains ongoing and, as of 2025, no convictions have yet been made.

In Brazil’s Amazon Basin, particularly in the states of Pará, Roraima, Rondônia, and Amazonas, many illegal miners operate with the backing or direct involvement of narcotrafficking organissations. According to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, criminal syndicates such as Comando Vermelho and regional Drug Trafficking networks have begun investing heavily in illegal gold mining as both a revenue stream and a means of laundering drug profits. These groups finance dredging equipment, provide security for mining camps, and use clandestine airstrips to move both gold and drugs through remote jungle corridors. In regions like Itaituba (Pará) and São Félix do Xingu, drug traffickers have established control over entire stretches of river where gold is extracted using mercury and high-pressure hoses, causing widespread deforestation and water contamination. Gold is then laundered through small-scale miners and front companies, often ending up in legal supply chains with falsified documentation. Authorities have identified that these operations also serve as logistical hubs for trafficking cocaine from Peru and Colombia into Brazil, with gold acting as a low-risk form of currency that is easier to transport and harder to trace than cash.

In Argentina's Catamarca province, lithium mining operations at the Salar del Hombre Muerto have been linked to the drying up of the Los Patos River, a critical water source for local communities and ecosystems. The extraction process consumes vast amounts of water, exacerbating scarcity in this arid region. In 2021, local NGOs filed a lawsuit alleging that the government of Catamarca did not carry out “an environmental impact assessment that contemplates the cumulative effects” of lithium mining operations. In response to environmental concerns, in 2024, an Argentine court suspended new mining permits in the area, mandating comprehensive environmental impact assessments before any further development.

Bolivia’s gold export system has become a key channel for laundering illegally mined gold, much of it sourced from the Amazon and sometimes smuggled in from neighbouring countries. Export companies frequently exploit the country's weak tracking mechanisms and self-declared documentation system to disguise the origins of gold. In a high-profile case, Goldshine SRL was caught in 2020 attempting to smuggle 331kg of gold worth US$18 million to Dubai using falsified export documents. Though the company’s owner, Amit Dixit, was under investigation, authorities later returned the confiscated gold and allowed him to export an additional 278kg before he fled the country. While US buyers once dominated Bolivia’s gold imports, they were largely replaced by buyers in India and the United Arab Emirates after US authorities began cracking down on illicit gold imports and increased scrutiny on origin verification. In contrast, Indian and United Arab Emirates buyers are known to pay quickly and ask few questions, providing an attractive market for exporters seeking to offload suspect gold.

A 2023 investigatory report by Greenpeace reported that 75 excavators made by Hyundai Construction Equipment were found to be in use by illegal gold miners to deforest land within the Indigenous lands of the Yanomami, Munduruku, and Kayapó. Illegal mining activities have led to a humanitarian crisis in these areas and companies, by selling equipment to these operations, risk being complicit in these crimes. One year later, in June 2024, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre stated that Hyundai and Caterpillar Inc. are facing significant reputational risks as reports of their machinery being used in illegal mining activities in the Amazon continue to come to light. Between April 2023 and 2024, for or example, 90 backhoes were seized on Indigenous and protected land – 26 of which were manufactured by Hyundai – with the use of such heavy machinery being tied to escalating illegal mining activities in the region. In response to questions from reporters, Hyundai clarified that it has a rigorous internal sales process in place to block customers suspected of involvement in illegal mining activities, and that it requires all customers to declare that the equipment will not be used for illegal mining purposes. However, Hyundai is reliant upon local distributors – in this case BMC Máquinas – to operationalise its standards, and as highlighted by other equipment manufacturers, it becomes difficult to monitor machinery as operators frequently remove trackers from them when entering protected areas. This highlights the importance of transparency and dedication to tackling illegal mining at all points of the supply chain.

In 2015, a cyanide solution spill at the Veladero gold mine, operated by Barrick Gold in Argentina’s San Juan province, contaminated local waterways and raised major environmental concerns. Authorities charged four officials in 2018 for failing to prevent the disaster, but as of 2025, no trial has occurred. Ricardo Villalba, the former director of IANIGLA, the national institute for glacier research, and former environment secretaries Omar Judis, Sergio Lorusso and Juan José Mussi were indicted for failing to oversee the National Glacier Inventory. According to court documents, many ice bodies that exist in the Lama-Veladero area, where Barrick Gold’s mine is located, were never inventoried, meaning they were never protected. The plaintiffs argued that had the inventory been completed properly, the Veladero mine would not have been allowed to operate and the cyanide spills would have been avoided. The officials are also charged with negligently withholding information and delaying the publication of the inventory, as well as postponing surveying work in the area near Barrick Gold’s mine. Community groups continue to demand accountability, while critics highlight the case as emblematic of regulatory weakness and corporate impunity in Argentina’s mining sector.

Bolivia’s small-scale mining cooperatives, particularly those in the La Paz region, wield immense political and economic power, enabling them to operate with near impunity. Originally created to support unemployed miners, these cooperatives have morphed into quasi-mafias, often acting as fronts for illegal operations run by Colombian and Chinese financiers. They exploit legal loopholes – such as weak oversight by the Jurisdictional Mining Administrative Authority (AJAM) – to mine in protected areas and avoid taxes. Many operate without environmental licenses, despite controlling 94% of Bolivia’s gold production, and use destructive techniques like massive dredging barges and mercury separation. Their influence has even allowed them to violently oppose government regulation, most notably in 2016 when protesting cooperative miners kidnapped and killed the deputy interior minister.

While mining - both legal and illegal - is generally considered a male-dominated occupation, women are also present in the mining workforce in growing numbers. In particular, women, who (in some regions) are often excluded from physically intensive and traditionally masculine roles, may instead resort to illegal mining. This is exacerbated by the caretaker burdens that often fall to women in communities where men die young from working in the mines or from alcoholism. In Bolivia, for example, half of the female mining workforce is made up of divorced, widowed and single women with children, who are increasingly turning to illegal mining to provide for their families. Some work underground, penetrating mines at night, while others sort through discarded chunks of ore in the outskirts of mines. This illegal work is frequently under the control or influence of criminal networks. Women may be forced to pay “access fees” to informal mine bosses or be subject to exploitation, including transactional sex, in exchange for mining access or protection.

Charcoal is the most important energy source in Somalia, relied upon by 98% of all households in towns and cities for heating and cooking. A recent investigation by CORRECTIV indicates that the charcoal trade contributes to the large-scale deforestation of acacia forests, which is concentrated in the regions of Jubaland, Lower Shabelle and Bay. The situation is particularly grave in Bay, where the trade is rapidly accelerating soil erosion and desertification - fueling drought and starvation among the local population. In addition to causing environmental degradation, the charcoal trade constitutes a significant source of terrorist financing. Large parts of the charcoal trade are under the control of jihadist organisation, Al-Shabaab, which uses the multi-million-dollar revenue generated by this trade to wage war on the Somali government, perpetuating regional instability and violence. As well as being victims to Al-Shabaab's brutality, local people are also vulnerable to illicit taxation and extortion by this group. The charcoal trade is also connected to money-laundering, with profits from the illegal charcoal trade being laundered to conceal their illicit origins. Although the production of charcoal and its trade for export was outlawed by the Somali government in 2012, CORRECTIV's investigation uncovers state corruption and complicity in the industry. Large charcoal production facilities are located in government controlled-areas and Somali officials, across various levels, benefit from this trade through the taking of bribes. The Somali army, for example, demands its own 'tax', in exchange for turning a blind eye to the transport of this resource in government-controlled territory from areas under Al-Shabaab-control.

Transparency International's report focuses on allegations of corruption and organised crime linked to Zambia's Mukula trade, a valuable timber species. The investigation reveals widespread fraud and collusion involving government officials, timber traders, and organised crime syndicates. These groups exploit loopholes in regulations to illegally harvest and export Mukula timber, evading taxes and enriching themselves at the expense of Zambia's forests and economy. The report highlights how corruption undermines efforts to sustainably manage natural resources, exacerbating environmental degradation and depriving the country of revenue that could support development. It calls for a comprehensive investigation into these allegations, urging authorities to prosecute those involved and strengthen governance mechanisms to prevent future abuses. Transparency International emphasises the importance of transparency, accountability, and international cooperation to combat organised crime and corruption in Zambia's timber industry, safeguarding natural resources and promoting sustainable development.

The Environmental Crimes Financial Toolkit is developed by WWF and Themis, with support from the Climate Solutions Partnership (CSP). The CSP is a philanthropic collaboration between HSBC, WRI and WWF, with a global network of local partners, aiming at scaling up innovative nature-based solutions, and supporting the transition of the energy sector to renewables in Asia, by combining our resources, knowledge, and insight.