.png)

The global illicit drug trade is booming, driven by surging supply and lucrative profit margins. The Persian Gulf has been swept into the heart of this drug trade boom—exploited as a trafficking corridor and, increasingly, targeted as an emerging consumer market.

In the first three months of 2025 alone, a major international security operation involving several Gulf states’ law enforcement seized over $2.9 billion worth of illicit drugs and arrested more than 12,000 individuals.

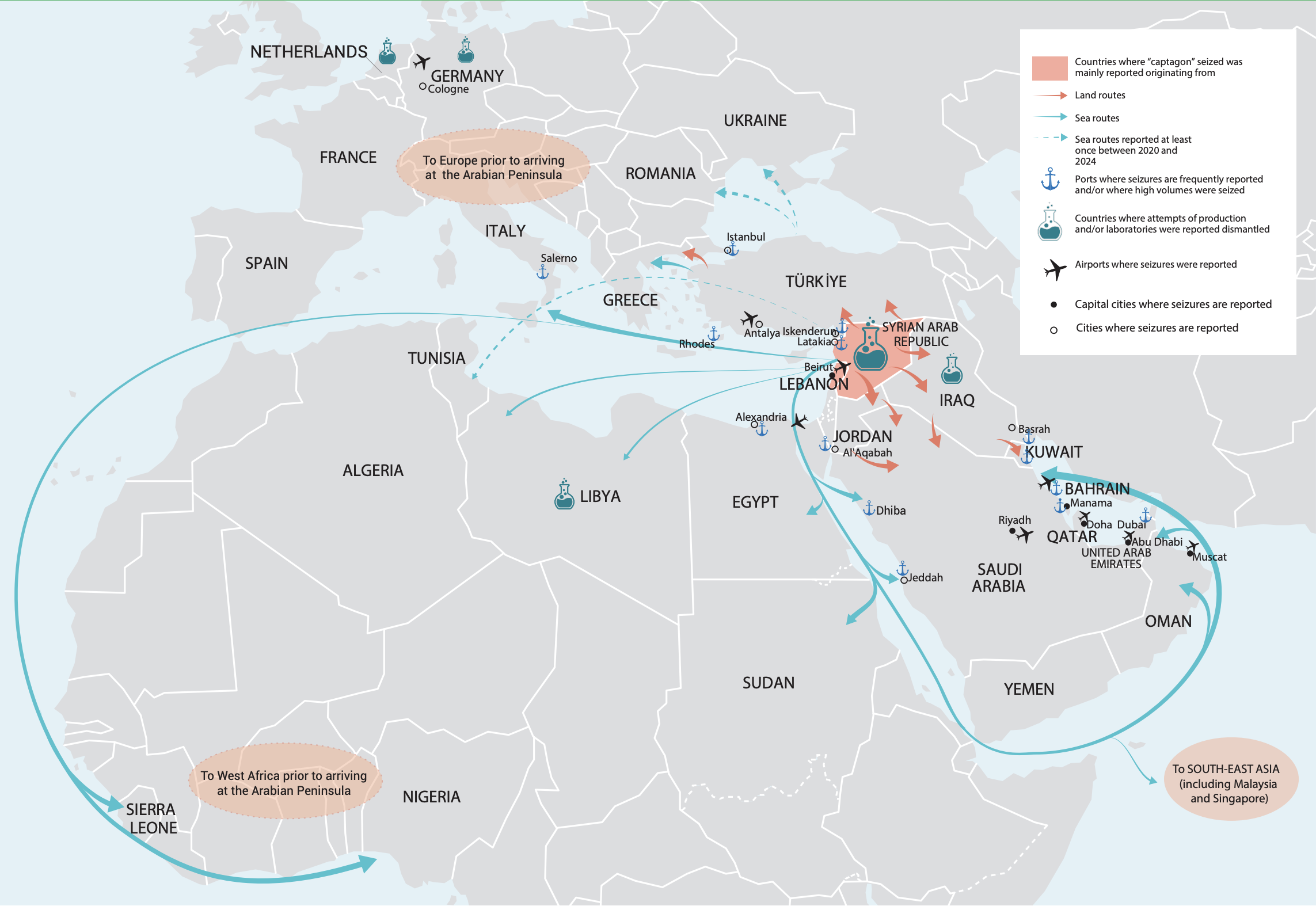

This staggering haul highlights not only the scale of the global drug trade, but also the Gulf’s growing exposure. Caught between major production zones and high-demand markets, the region has become a strategic transit point—its combination of land and sea routes offering traffickers an ideal gateway for moving illicit goods.

Criminal networks are taking advantage of the Gulf’s open economies and sophisticated trade systems; in other words, infrastructure built for business now inadvertently facilitates the movement of illicit drugs. Key shipping routes around Gulf countries—including the Arabian Sea, Gulf of Oman, Gulf of Aden, and the Red Sea—give traffickers access to global markets. Reflecting this heightened risk, INTERPOL has enhanced maritime operations in the region, including a specific programme for combating drug trafficking in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

The illicit drug trade also threatens regional security and financial integrity. The same criminal networks exploiting the Gulf’s trade infrastructure are also targeting its financial systems to launder money and fund operations. These illicit financial flows are often tied to other regional crime, conflict and instability.

As new threats surge across the Gulf, countries in the region must closely monitor the trends that leave them most exposed. Here are four key trends we’re watching.

One of the most alarming trends experts are tracking is the shift in maritime drug trafficking tactics in the Gulf. In line with global trends, criminal groups are adopting more sophisticated, large-volume operations using commercial vessels. This shift is likely driven by a multitude of factors, including a rising appetite for risk and the lure of substantial financial returns—particularly as today’s global illicit drug trade generates hundreds of billions of dollars annually, making it an increasingly attractive venture for criminal networks seeking high-profit, high-reward opportunities.

These criminal groups are also investing heavily in their illicit supply chains, including directly purchasing commercial shipping vessels directly. The BBC found, for instance, that a network linked to the notorious Kinahan crime family—which operates globally, including in the Gulf—acquired a £10 million vessel to support its drug trafficking operations.

This underscores the growing sophistication of trafficking networks, with criminal groups now investing directly in logistics which enable them to bypass traditional checks and balances. The impact of this shift goes far beyond the ability to move more drugs at scale—the increasing use of legitimate shipping vessels and infrastructure also poses serious enforcement challenges.

One of the most worrying of these challenges is the legal protections that commercial ships enjoy as flagged ships; vessels flying under a national flag are protected under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) from being boarded by foreign states without flag-state consent. Smaller boats such as traditional fishing dhows used to traffic goods in the Gulf do not fall under these same protections, meaning commercial ships are harder for transnational maritime coalitions to intercept and board.

This added protection may not just be a fortunate side effect for traffickers who have shifted to more commercial vessels but one of the key motivations for adopting this shift in the first place.

Another growing trend in the Gulf is the rise of new players in the Middle East’s Captagon trade. With the fall of the Assad regime in 2024, both the production and trafficking of Captagon have entered new phases. Using the Captagon trade as a financial lifeline amid the levying of intense sanctions and economic struggles, the Assad regime was the primary force behind the production and trafficking of the drug until recently.

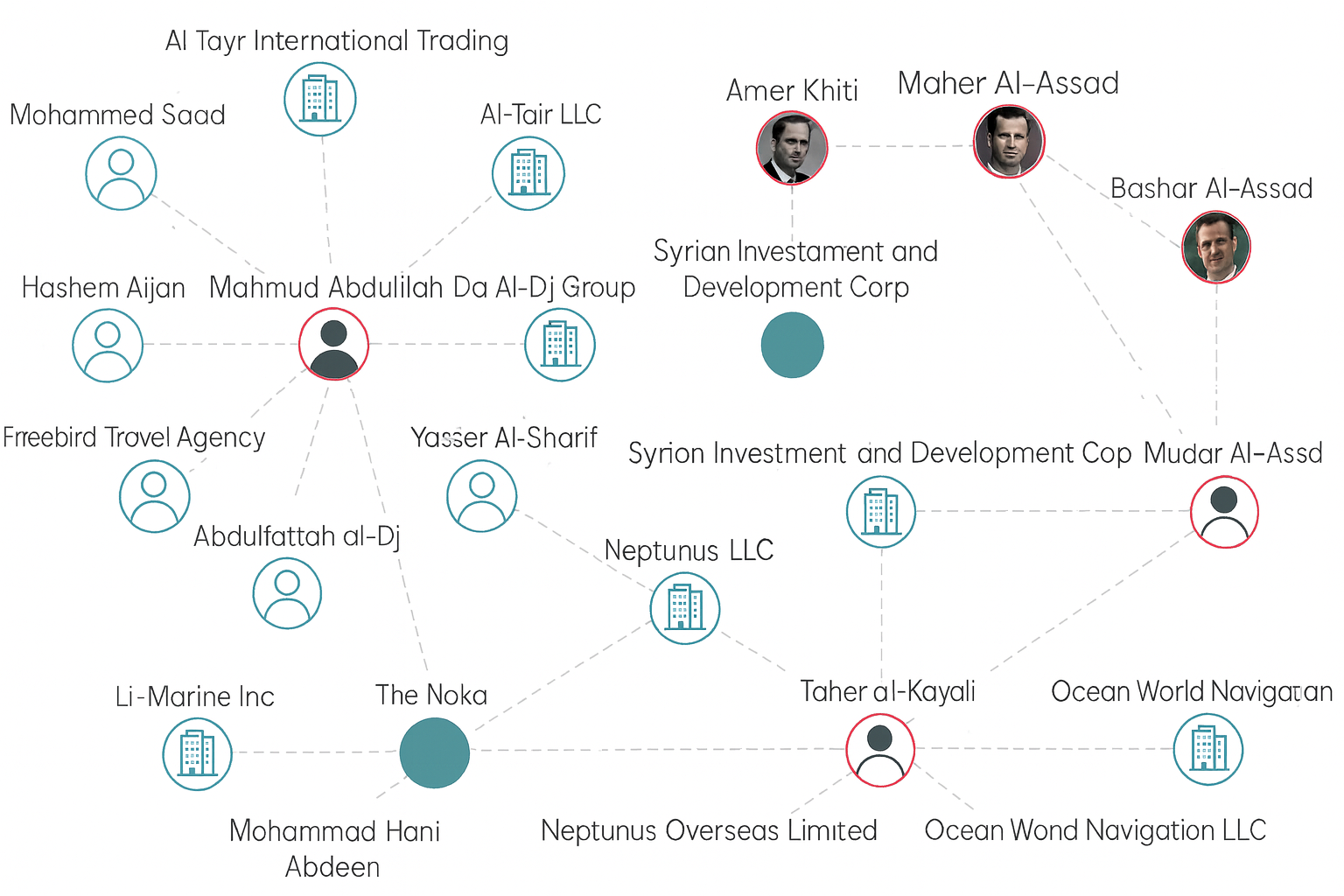

The commander of the regime’s Fourth Division, Maher al-Assad—brother of former President Bashar—was reportedly a key leader in this illegal trade, as was Hezbollah, in Lebanon. This links the huge profits from this drug to regional instability and conflict financing, as well as other illicit finance dealings such as property purchased with the proceeds of Captagon.

The Gulf region is a major consumer market and transit hub for Captagon, with Saudi Arabia frequently identified as the world’s largest market for the drug. Authorities in the Kingdom regularly intercept shipments containing over a million pills, underscoring the scale of the trade and the challenges faced in combating it. Moreover, all Gulf countries have seen a rise in demand among young people over the past couple of years. Gulf ports are also leveraged as transit points for Captagon entering other markets.

Since the Assad regime’s collapse, and with ongoing efforts by the new Syrian government to stamp out Captagon production domestically (although with limited success), new production sites have popped up regionally—followed by new trafficking routes. This leaves the Gulf vulnerable to new risks related to the Captagon trade, complicating law enforcement efforts, just as authorities were coming to grips with some of the now diminishing players and tactics linked to the trade.

One of the most alarming developments for Gulf countries is the reportedly increasing role Houthi-controlled areas in Yemen are playing in Captagon production.

Moreover, Yemeni authorities have suggested that the Iranian regime is serving as the primary financier and coordinator forHouthi-established production, including the establishment of production facilities and regional trafficking networks.

Another key trend to note is the surge of meth trafficking across the Middle East, with the UNODC reporting a sharp increase in meth seizures in Afghanistan and neighbouring countries. Experts have particularly highlighted a rise in meth trafficking from Afghanistan and along the Pakistani coast (where meth busts jumped nearly sevenfold in just a single year). Iran has also seen growth in meth trafficking, and heightened regional production of the drug could continue to heighten Iran’s role in meth trafficking.

Concerningly, Pakistan and neighbouring India are also becoming key trafficking hubs for precursor chemicals used in meth production, with the U.S. State Department identifying both as major source countries for precursor chemicals. This trend poses serious regional and global security risks, since precursor trafficking networks can be linked to extremist groups or terrorists, including the financing of these groups.

This surge in meth production in the Golden Crescent region is particularly concerning for Gulf countries as they lie directly along key smuggling routes for this region. For instance, over the last decade, Iran comprised the main source of illicit drugs smuggled intoBahrain; an increase in meth trafficking linked to Iran could spell an influx into—and trouble for—Bahrain.

.png)

Threats from theGulf’s illicit drug trade extend far beyond the region. A major concern is the involvement of European organised crime groups and their illicit networks. European ports have become key transshipment hubs for Captagon and meth routed from the Middle East to the Gulf. Traffickers exploit EU port documentation—particularly customs stamps—to bypass stricter inspections atGulf ports that target direct shipments from the Middle East.

Additionally, Mediterranean criminal networks provide financial, commercial, and operational support to Gulf-related drug trafficking. A notable example is the 2018 interception of the cargo ship Noka by the Greek Coast Guard.

An internal Themis investigation, detailed below, shows direct ties between this shipment and the Assad regime’s former Captagon enterprise, highlighting the global nature of the threat and the blurring of lines between transnational criminal networks and corrupt state-sponsored actors. European intermediaries, trade infrastructure, and financial systems are not only being exploited to enable drug trafficking from the Middle East but may also be inadvertently supporting conflict financing and other forms of destabilising activity across the region.

Our analysis underscores the urgent need for a coordinated strategy to combat transnational crime and illicit finance in the Gulf. At Themis, we support both public and private sectors in developing collaborative, cross-sector solutions to address these challenges. We also offer tailored technology solutions designed specifically to address the nexus of illicit finance and transnational crime.

It’s time to connect the dots — with smarter tech, sharperskills, and stronger partnerships.

This article explains how data and analytics are used to detect insurance fraud more effectively.

This article explains ghost broking, a form of insurance fraud that targets victims through fake policies.

This article explains how machine learning improves fraud detection by identifying complex patterns at scale and adapting to evolving threats.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript