Cobalt is one of the world’s most important natural resources and also one of the most controversial, having become near synonymous with both environmental and human exploitation. Consumers worldwide, particularly in developed countries, are inevitably bound up in cobalt’s opaque supply chains through their dependence on electronic devices. This blog examines the global demand driving cobalt extraction, outlining its central role in modern technology and analysing recent trade data to reveal how and where it is processed. In doing so, it extends accountability for cobalt’s human and environmental costs beyond mining sites and African borders.

To understand the world’s growing fascination with cobalt—a ‘critical’, ‘conflict’, or ‘blood’ mineral, depending on who you ask—it is important firstly to understand the lithium-ion battery.

A lithium-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery, known for having higher energy efficiency and a longer life cycle than other types of rechargeable batteries. Since being introduced to the market in 1991, technological innovation has furthered this efficiency while reducing cost, with the invention and commercialisation of lithium-ion batteries recognised by a Nobel Prize in 2019.

The electronics and digital infrastructure that are now ubiquitous and crucial to modern day society, such as laptop computers, mobile phones, electric cars and energy storage at grid-scale, all rely on lithium-ion batteries.

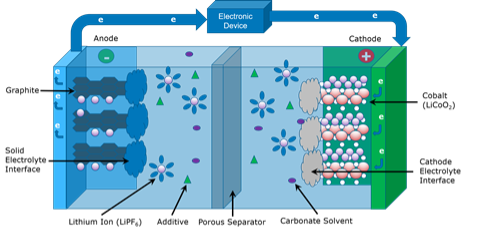

A detailed—but brief—science lesson on these batteries: they are made up of two electrodes: a positively charged cathode; and a negatively charged anode, which are immersed in an electrolyte solution and separated by a permeable membrane that ions can travel through. When a battery is charging, electrically charged lithium-ions pass from the cathode to the anode. When they discharge, for example when charging a phone, the ions travel back from the anode to the cathode, and in this process they release electrons that generate the electrical current used by the device.

This is where cobalt comes in. As lithium-ions move through the battery in and out of the anode and cathode, the charge of these electrodes changes. The role of cobalt is to compensate for the charge when these lithium-ions move in and out, ensuring that the structure remains stable and the battery behaves predictably. Cobalt in lithium-ion batteries is also associated with improved performance compared to other materials like manganese or iron, allowing batteries to be simultaneously smaller and more powerful.

Around half of the cobalt produced globally currently goes into making lithium-ion batteries, though it is also used more generally in advanced semiconductors and jet turbines. Consequently, it is widely considered a critical mineral, upon which the electronic infrastructure of contemporary society relies. However, this demand for cobalt has also been associated with violence, abuse and widespread negative environmental and social impacts, most notably at the point of extraction—namely the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

Cobalt mining in the DRC is fraught with issues and is the subject of increasing public attention. Significant use of child labour in Congolese cobalt mines has been recorded, often under dangerous conditions. Indeed, the deaths of children mining for cobalt in the DRC was the subject of a 2019 lawsuit brought against companies such as Apple, Tesla and Google by Congolese families who say their children were killed or maimed while mining for cobalt. Cobalt mining has also been linked to chemical poisoning, with chemical runoff polluting the surrounding environment and threatening human health. Experts also estimate that millions of trees have been cut down in the DRC to enable cobalt extraction. All of this has contributed to the introduction of the moniker ‘blood cobalt’.

On top of immediate social and environmental impacts, cobalt mining in the DRC is also associated with corruption and bribery, fraud, tax evasion and conflict financing. At a grand scale, corruption enables continual siphoning of revenue from the country to foreign companies. In 2022, Swiss mining conglomerate Glencore was convicted of paying at least USD 27.5 million in bribes to gain business advantages in the DRC, and in the same year, the audit of Gécamines, DRC’s state-owned mining company, revealed embezzlement of tax payments, excessive subcontracting with parent company subsidiaries and selling products at discounted prices.

Cobalt, particularly when illegally mined or associated with problematic labour practices, is often smuggled out of the DRC to be exported under a nominally different (and ‘cleaner’) point of origin, aided by corruption at the borders with Zambia, Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania. Moreover, in many places, cobalt mining is controlled by armed groups which utilise the profits to prop up their operations.

Despite the widespread and increasingly widely known issues associated with cobalt mining in the DRC, it continues to supply over half of the world’s cobalt, meaning that the responsibility for environmental and human rights violations associated with cobalt extraction stretches far beyond the DRC.

Indeed, an analysis of trade data from 2023 reveals that DRC cobalt likely enters end markets such as the US, Germany, Korea, the Netherlands and Japan in the form of lithium-ion batteries that are produced in China. Given the difficulties in determining whether cobalt is, truly, ‘clean’ of associations with conflict, child labour and fraud, it is highly likely that companies—and consumers—operating out of countries with ostensibly high human rights standards are purchasing products produced with ‘blood cobalt’. The electric vehicle industry is a key sector, with major companies such as Tesla, GM, Ford, BMW, Toyota, Hyundai and many others based in countries that are consuming large volumes of Chinese lithium-ion batteries.

As the 2019 lawsuit on child labourer deaths against US tech companies demonstrates, pressure is growing on the end-users whose demand fuels exploitative extractive practices. This heightened scrutiny is not limited to corporations but also implicates the banks that enable corporate operations through financial backing and assurances. In light of novel litigation cases that now target the banks that finance corporations committing environmental violations, the financial sector should also weigh the potential reputational costs of being associated with problematic mining practices, and utilise their significant influence as financiers to encourage their clients to instate fairer, more transparent and safer supply chains.

Financial institutions and businesses exposed to high-risk commodity supply chains need practical tools to identify hidden risks before they escalate into regulatory sanctions or reputational damage. Themis offers both technology and strategic intelligence to uncover these exposures:

Compliance jargon is packed with ever-multiplying KYA acronyms. This blog explores where they came from, what they actually mean, and why understanding them matters, blending humour with practical insight to help you navigate the acronym jungle.

A discussion of how fraud damages brand reputation, customer trust and long-term growth.

This article explains how data and analytics are used to detect insurance fraud more effectively.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. Ut enim ad minim veniam, quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat. Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur.

Block quote

Ordered list

Unordered list

Bold text

Emphasis

Superscript

Subscript